Introduction

The invention of the internet and its associated tools specifically, “social media platforms” have made leisure and communication easier and faster than in previous years.

Social media can be defined as ‘web-based services that allow individuals to construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection and view and transverse their list of connections and those made by others within the systems[1]

Simply, social media is a medium that can be used to create and share content while interacting with other users who share common interests. Unsurprisingly, these tools have become an integral part of life, and it is almost uncommon to meet a person who does not use any.

The frequency of its use has led some scholars to argue that access to the internet should be considered a basic human right. Their position is premised on the fact that the use of the internet improves the exercise of other rights including the right to freedom of speech and expression, the right to privacy, the right to education and the right to information guaranteed as in the laws of many jurisdictions.

More relevant to this article is the dynamic created by the use of social media usage on the employer-employee relationship. The lines between private and professional life have somewhat been blurred by the fact that working colleagues occasionally interact on these platforms with some employees posting about their workplaces. The result is that the employee’s identity and actions get linked with the brand image of their employers.

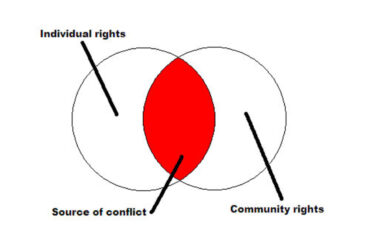

Whereas these interactions can create a general sense of belonging and comradeship for employees a conflict may arise between the employer’s right to protect his brand image and the employee’s rights to freedom of expression and privacy.

This article looks at whether employees can incur liabilities from their employers for their social media activities within the context of the current legal framework of Ghana. The article is structured in three parts; the first part gives an overview of employment/labour law in Ghana; the second part focuses on the right to termination and the third part discusses whether social media conduct would constitute a valid ground for termination.

OVERVIEW OF THE EMPLOYMENT LAW

The law that governs the rights and responsibilities of parties in an employment relationship is a convergence of the law of contract and Statute. The employment contract is fundamental because it is what confers the status [2] of the parties in the relationship and like any other type of contract may be either written or oral. Depending on the jurisdiction, different statutes may govern the employment relationship but predominately such laws are known as Labour laws. An employment contract is also essential in responding to gaps in the existing law by providing for situations that have yet to be legislated on.

In some employment relationships, there may be what is known as collective agreement [3]. This is usually the product of bargaining between the employees through an association or union of workers and their employer. At common law, a collective agreement is not legally enforceable and would not automatically become part of the individual contracts of employment made between employers and their employees [4]. However, under Ghanaian law, provisions contained in a collective agreement are deemed as a term of the personal contract of employment each employee has with the common employer.

The primary legislation governing employment relationships in Ghana is the Labour Act, 2003.[5] The purpose of the Act is to address the imbalances of the power structure between the employee and his employer through provisions that protect the rights of both parties[6] and those that state their duties towards each other[7]. These provisions are instructive for the conduct of the relationship or ending it. The employer, for instance, has a right to employ, discipline, transfer, promote and terminate the employment of the worker. While the employee is entitled to work under safe conditions and to be paid equally for work done.

Generally, the commencement and end of an employment relationship may be by mutual consent. This is usually when the employment is for a specific period or is determinable at the occurrence of an event. However, the end of an employment relationship may also be occasioned by a unilateral decision, that is where the employee resigns, or the employer terminates the relationship or dismisses the employee. Given that people’s livelihoods[AA1] are dependent on income and benefits that are attached to their employment, it is no surprise that one of the most litigated matters under employment law is whether a termination or dismissal is lawful.

- THE RIGHT OF TERMINATION

Implied in every employment relationship is the right of either the employee or employer to bring the relationship to an end[8]. The Labour Act[9] also protects this right by giving grounds for which employment may be terminated. Such instances include mutual agreement, stated misconduct, and the death of the employee.

In Aryee v State Construction Corporation,[10] the court held that “a contract of service is not a contract of servitude…the contract is framed in a way that either party may bring it to an end and free himself from the relationship painlessly”.

Also, in Kobeah v Tema Oil Refinery, this right is stated as follows;

“At common law, an employer and his employee are free and equal parties to the contract of employment. Hence, either party has the right to bring the contract to an end per its terms. Thus, an employer is legally entitled to terminate an employee whenever he wishes and for whatever reasons, provided only that he gives due notice to the employee or pay him his wages in place of the notice…. He does not even have to reveal his reason, much less to justify the termination”.

The position of the law is that each party need not give reasons for why he wishes to end the employment relation. Notwithstanding that, where termination is premised on alleged misconduct[11] by the employee, the employer must show that he has a substantive right to termination at the occurrence of the act and that the proper procedure was followed[12].

Consequently, an employee must be told of his alleged misconduct and his defence or explanation heard before any decisions are taken [13]. However, where the misconduct is grave, the employer has a right to summarily dismissal [14], that is an instant dismissal without complying with any procedure. Termination of employment because of social media activities may be treated as misconduct entitling the employer to terminate the relationship.

MISCONDUCT

The Labour Act does not define the word “misconduct” thereby it gives employers wide discretion to set the criteria for what categories of activities will fall within this description. Whatever acts the employer seeks to regulate must however be reasonable because people exercising discretionary power are required to exercise it fairly and candidly[15]. Where employers refrain from setting a criterion, they have invariably left that determination to judicial interpretation when disputes of unlawful termination arise.

Typically, a misconduct will be an act that is in itself serious or has serious consequences on the profitability of the business or its brand image or makes it difficult for the employee to satisfactorily continue his employment[16]. The severity of the act may be sufficient justification for an employer’s prohibition of the act either at the workplace or during work hours.

Ordinarily, employee misconduct entitles an employer to interdict the employee for further investigations or demand a written explanation from the worker before a decision to terminate or dismiss the employee is made [17]. It is therefore desirable that an employer clearly states what is or is not acceptable behaviour for members of the organization.

SOCIAL MEDIA POLICY AND STATED MISCONDUCT

The employer’s provision for acceptable conduct including social media usage guidelines may be justified on grounds that the employee is obliged to obey the commands of his superior[18]. Guidelines may be stated in either the employment contract or in a collective agreement[19] and where expressly provided for, a breach would give the employer the substantive right to dismiss the offending employee. The dismissal must however follow laid down procedures which afford the employee a chance to be heard before he is dismissed[20] else it may be voided by a court.

The necessity of stating that some social media conduct would constitute misconduct is because this area of the law is still being developed and the courts are more likely to uphold the right to freedom of expression given that is the bedrock of democracy.

For instance, in Morgan v Parkinson Howard Ltd[21], the court held that an employee who claims he has been wrongfully dismissed would have to prove that the dismissal was in breach of the terms of his agreement or a statutory provision regulating employment. Therefore, an employer who wishes to avoid liability for unlawful dismissal must be proactive in including social media policies in the terms of employment.

Also, the social media policy of the employer may extend outside of the working environment or work hours so long as it is reasonable.

In McManus v Scott[22] the court held that employees have an implied duty to obey reasonable and lawful commands relating to out-of-hours conduct where these conducts have been demonstrated to have a substantial and adverse effect on the employer’s business.

Another emerging issue related to social media usage is where the public “calls out”[23] employers to hold their employees accountable for their social media activity. By so doing, customers require employers to take a stance that disassociates their brand image from the wrong the employee is alleged to have committed [24]. This public pressure may lead to the dismissal of the employee and the employer may defend himself in any action by saying that he was acting to protect his interests.

While there is no precedent under Ghanaian jurisprudence, it seems that a judicial pronouncement on the lawfulness of a dismissal based on such public pressure would be dependent on whether the employer can rely on a social media policy prohibiting the act and in the absence of that, whether the act was so grave that it would fall under the statutory provision for misconduct.

Although it is of persuasive effect in Ghanaian courts, a clear example of this is in Game Retail Ltd v Laws [25] where it was held by the employment tribunal that in the absence of a social media policy that stated what was inappropriate activity, the dismissal of the employee was unfair. Thus, in that case, the nature of the act was not of prime consideration for the court rather the absence of a policy was the deciding factor.

CONCLUSION

Whereas any of the parties in an employment relationship may bring the relationship to an end, a termination by an employer may be held to be an unlawful dismissal if he fails to justify it under the grounds stated in the Act or the employment contract. As would a failure to comply with the required procedure. Also, an employee who feels aggrieved by a termination may seek the remedies of restitution and damages in an action against the employee.

Given that the use of the internet and social media encourages the exercise of freedom of speech, it is recommended that employers consider other forms of discipline where the alleged misconduct is not grave.

[1]van Dissel, Beatrix M. P. (2014). Social media and the employee’s right to privacy in Australia. International Data Privacy Law, 4(3), 222-234.

[2] The employment agreement may create any of the different types of employee status recognized by law namely employee, casual laborers, and temporary workers.

[3] SECTIONS 105, 110 LABOUR ACT, 2003 AND GEORGE AKPASS V. GHANA COMMERCIAL BANK LTD. (2021) JELR 108741 (SC)

[4] KOBEAH AND OTHERS V. TEMA OIL REFINERY; BOATENG AND OTHERS V. TEMA OIL REFINERY (CONSOLIDATED) (2004) JELR 68323 (SC)

[5] LABOUR ACT, 2003 (ACT 651)

[6] SECTIONS 8 AND 10

[7] SECTIONS 9 AND 11

[8] KOBEAH AND OTHERS V. TEMA OIL REFINERY; BOATENG AND OTHERS V. TEMA OIL REFINERY (CONSOLIDATED) (2004) JELR 68323 (SC)

[9] SECTION 15

[10] ARYEE V. STATE CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (1985) JELR 67210 (CA)

[11] SECTION 62 OF LABOUR ACT

[12] GEORGE AKPASS V. GHANA COMMERCIAL BANK LTD. (2021) JELR 108741 (SC)

[13] KOBEAH AND OTHERS V. TEMA OIL REFINERY; BOATENG AND OTHERS V. TEMA OIL REFINERY (CONSOLIDATED) (2004) JELR 68323 (SC)

[14] In LEVER BROTHERS GHANA LTD V ANNAN; LEVER BROTHERS GHANA LTD V DANKWA (CONSOLIDATED) (1989) JELR 68077 (SC) the court stated that where the misconduct is so grave it may justify an instant dismissal and the employer can rely on that misconduct in defence of any action for wrongful dismissal. The employer is in this instance not required to set up an investigative process.

[14] It may also be contained in the employee’s handbook, policies or regulations.

[15] ARTICLE 296 OF THE 1992 CONSTITUTION

[16] LEVER BROTHERS GHANA LTD V ANNAN; LEVER BROTHERS GHANA LTD V DANKWA (CONSOLIDATED) (1989) JELR 68077 (SC) and Streeter v Telstra Corporation Limited (U2007/3324) [2008] AIRCFB 15

[17] GEORGE AKPASS V. GHANA COMMERCIAL BANK LTD. (2021) JELR 108741 (SC)

[18] YAOKUMAH V THE REPUBLIC (1976) JELR 65664 (CA)

[19] It may also be contained in the employee’s handbook, policies or regulations.

[20] ARYEE V. STATE CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (1985) JELR 67210 (CA): the chance may be given either through written correspondence or the employee may be invited for a physical meeting to give his explanations or answers.

[21] MORGAN AND OTHERS V. PARKINSON HOWARD LTD (1961) JELR 69542 (HC)

[22] (1966) 140 ALR 625

[23] This is where other users of social media try to hold a person accountable for their actions by seeking punitive actions from the offending user’s employer.

[24] SEYI OMOOBA v. MICHAEL GARRETT ASSOCIATES (T/A GLOBAL ARTISTS) & LEICESTER THEATER TRUST LTD (2024) JELR 111477: an actress was removed from a movie production because of public backlash for homophobic comments made on her Twitter Account.

[25] GAME RETAIL LIMITED V. MR C LAWS (2014) JELR 111478

[AA1] Perhaps this is so because people’s livelihood is dependent on the income they earn from their jobs and depending on the job climate, the qualifications or age of the employee, the chances of finding an alternative employment may prove difficult.