Introduction

In the Black’s Law Dictionary[1], “privacy” is defined as the state of being free from public attention to intrusion into or interference with one’s acts or decisions. Simply the right of a person and his property to be free from unwarranted public scrutiny or exposure. This right is essential to all people because, despite the inherent human desire to be known and admired, there is an equally strong desire to keep certain matters out of the eyes of others.

The friction between these two desires comes out forcefully in the use of traditional media like Television and social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook. It is not uncommon, for instance, to find active social media users sharing their views on trending topics, posting personal pictures and videos showcasing the happenings in their lives voluntarily on their social media pages. However, there are instances where pictures and other personal information, about people are published without their consent.

While some of these posts gain positive comments and feedback from other social media users there may be an equally strong and negative backlash which can border on cyberbullying and in worse cases may lead to negative repercussions in a person’s real life.

In 2021 for instance, J.K Rowling[2] received severe criticism on social media for her controversial comments about the transgender community. Unfortunately, these attacks were not limited to just the internet as there were physical protests outside of her home resulting from someone posting a picture showing her home address.

In this article, I will be discussing the right to privacy and its scope, particularly within the Ghanaian context. Then in the latter part of the article, I will discuss the tension between the right to privacy and the right to freedom of expression and how the conflict may be resolved.

What does the right to privacy entail?

In law, the right to privacy connotes a variety of interests that the law may protect against an interference complained of. These interests include the freedom of personal autonomy, the right to control personal information, the right to control property, and the right to control and protect physical space[3]. A person who claims he is owed this right and seeks to enforce it may rely on a law such as a constitution or an Act of Parliament, a contractual agreement, or a tortious act.

A tort is a civil wrong for which the law will provide a remedy[4]. Usually, an action in torts is mounted when a person’s legal interest is interfered with in the absence of any contractual obligation placing an obligation on another to avoid interfering with the said right. Generally, the type of tort under which a person may be entitled to make a claim is dependent on what aspect of the complainant’s life or property has been affected by the interference.

When it comes to physical interference with life and property, the law readily gives a remedy under the torts of trespass, battery, and false imprisonment among others[5]. However, since common law has no tort of invasion of privacy[6], the types of torts under which the Courts have often tried to resolve cases relating to the interference of privacy include the tort of nuisance, negligence[7], trespass, and defamation[8]. By doing this, the courts can provide a remedy to a claimant who alleges that his private affairs have been intruded on, has been exposed to public ridicule by the disclosure of some private fact about his life, or that his name or likeness has been appropriated[9].

A contractual obligation to protect a person’s privacy arises when there is an agreement between two people to refrain from disclosing certain information that has come to their knowledge by a business or personal relationship. An example is the standard privacy policy and terms that users of a service or technology are required to consent to before use.

In some jurisdictions, the principle of reasonable expectation of privacy was developed to address violations of the right to privacy. The courts consider factors such as the nature of the private information, how the information was obtained, the purpose of the intrusion, and whether the information was already within the public domain[10].

Ghanaian jurisprudence on the right to privacy

The first reference point for issues relating to the right to privacy in Ghana is Article 18(2) of the 1992 Constitution which states that;

“No person shall be subjected to interference with the privacy of his home, property, correspondence or communication except by law and as may be necessary for a free and democratic society for public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the protection of health or morals, for the prevention of disorder or crime or the protection of the rights or freedoms of others.”

Thus, as the highest law in Ghana guarantees, any interference in the home, property, and any form of communication of a person that is not situated within the legally permissible context is a violation of their right.

Apart from the constitution, other legislation such as the Data Protection Act, of 2012 (Act 843), the Electronic Transactions Act, of 2008 (Act 772), Cybersecurity Act, of 2020 (Act 1038) also seek to protect a person’s privacy by regulating how personal data like residential addresses are used by third parties. Also, the Supreme Court has on several occasions been called upon to determine the ambit of this right within the context of certain alleged violations.

In Raphael Cubagee V. Michael Yeboah Asare & others[11] the Supreme Court held that the constitutional right to privacy is so broad that its full scope cannot be set out in the text of the Constitution. However, it covers an individual’s right to be left alone to live his life free from unwanted intrusion, scrutiny, and publicity. It is the right of a person to be secluded, secretive, and anonymous in society and to have control of intrusions into the sphere of his private life.

The contest between privacy and freedom of expression

The right to freely express oneself is core to the development of a personal identity and achieving a sense of self-fulfillment[12]. It enables a person to identify and be identified with certain ideas or values, contribute to debates about social and moral values, and have fun through communication.

In Ghanaian cases such as NPP V IGP[13] and Ghana Independent Broadcasters Association v Attorney General,[14]the Supreme Court stated that the right to freedom of expression is important in democratic societies because all other human rights and freedoms are hinged on it.

Traditional media like radio and television and more recently social media usage are some of the tools by which people have exercised this right. However, the increase in use and technological advancement in this field has added a new dimension to the conversation about privacy. Issues of copyright disputes, and infringement of a person’s right to an unsullied reputation, to mention a few, have cropped up concerning publications made on these varied mediums. Prevalently is where the privacy of a person is breached by their being unwittingly made the subject of the published content.

This usually occurs when audiovisual materials such as videos are taken of people without their consent and published as content. Another instance may be where private messages meant for a particular individual or group of individuals are shared with an audience not belonging to the intended recipients. Thankfully, the courts will not sanction an action that infringes on the rights of others or is against public policy even if it was done in the exercise of a person’s freedom of expression.

In Asantewa-Danquah v Scancom Limited[15], for instance, the court found the defendant’s employee to have violated the plaintiff’s rights by forwarding nude and confidential photos from her phone to himself when it was taken for repairs.

Also, in Raphael Cubagee V. Michael Yeboah Asare & others[16] the Supreme Court held that a secret recording of a private conversation is an interference with the privacy of the other person beyond what he has consented to.

Again, in Ikere v Standard Group Limited[17] the Kenyan Court held that the publication of the pictures of the children of a man described as “the most wanted criminal” violated their right to privacy and dignity while prejudicing their reputation.

With traditional media, the right to freedom of expression is jealously guarded both by local[18] and international law because of the role they play in promoting the principles of democracy.

For instance, Article 10 of The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms,1950[19] states that although states may prescribe licensing requirements on them, they must be free to hold opinions, receive and impart information without state interference except for where necessary in the interest of national security, prevention of disorder or crime, protection of the reputation or the rights of others amongst others.

The courts of various countries have been frequently called on to examine the clash of these rights particularly within the political sphere. For example in Lingens v Austria[20], the European Court of Human Rights stated that “while the press should not overstep the boundaries set, inter alia, for the protection of the reputation of others, it is nevertheless incumbent on it to impart information and ideas on political issues just as those in other areas of public interest… because the public has a right to receive them…freedom of political debate is at the very core of a democratic society…. The limits of acceptable criticism are accordingly wider as such than as regards a private individual.”

In Derbyshire County Council v Times Newspaper[21], Lord Keith also stated that “it is the highest public importance that a democratically elected government body should be open to uninhibited public criticism. The threat of a civil action for defamation must inevitably have an inhibiting effect on freedom of speech.”

Similarly in Ghana Independent Broadcasters Association v Attorney General,[22] the court held that freedom of expression ensures self-government, informed voting, and checks abuses of power. It also promotes the development of culture, science, and art. It also ensures individual self-development, association, and enjoyment of all other rights.

The courts take this position in matters involving political persons or bodies for reasons that allowing actions against the media may lead to wide public censure because the trickle-down effect would be that private individuals who criticize the government may find themselves saddled with defamatory actions. Similarly, every citizen should be free to criticize an inefficient government or public official without fear of civil or criminal liability.

How does the court resolve a conflict between two rights?

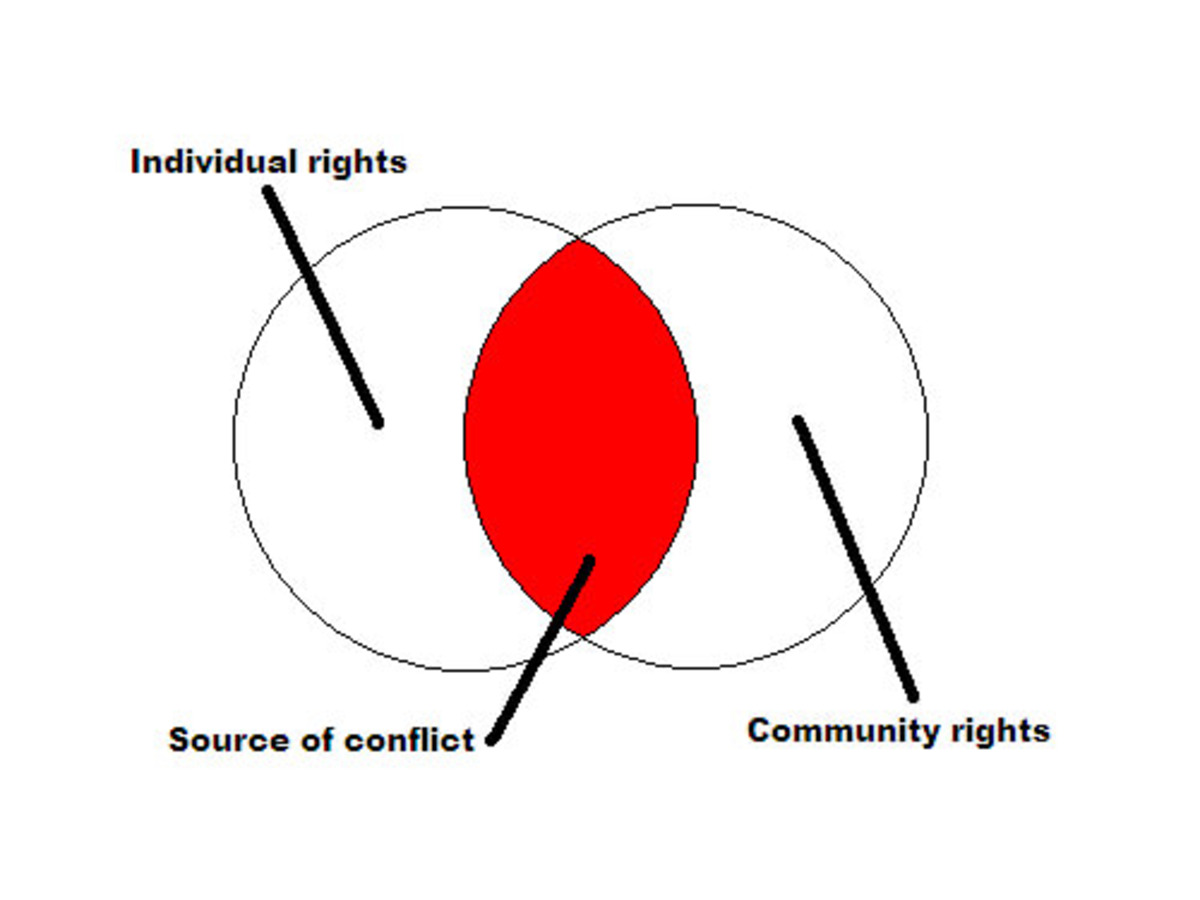

In determining whether there has been a breach of one’s rights the courts will apply a balancing test between the two competing rights along with other factors such as public policy considerations to the set of facts presented to them.

This is because Article 12[23] places a general restriction on the fundamental human rights guaranteed when there are public interest and public policy considerations or where necessary to protect the rights of others[24]. Thus, in determining whether a person’s privacy has been violated the courts are likely to strike a balance between the claimant’s right to privacy and the publisher’s right to freedom of expression.

Conclusion

In sum, the right to privacy is an essential right that requires protection because it ensures individuals are safe from intrusions and invasions in all aspects of their lives including their person, personal correspondence and communications, their home, and property. While the right to freedom of expression is necessary for the enjoyment of all other rights. When a conflict arises between these two rights, it can be resolved by exercising the right to freedom of expression in consideration of factors such as the rights of others or public policy.

Fortunately, the law provides a remedy for a person who believes his rights have been violated. The kind of cause of action he may bring would however depend on the relevant facts and the circumstances. Generally, for example, he may bring an action under the tort of defamation when the published content sullies his reputation in the eyes of right-thinking men of the society. Similarly, where private correspondence or conversation is recorded or shared with a third party, it would be deemed an intrusion into his privacy beyond what he has consented to, entitling him to commence a legal action to enforce his constitutional right or mount an action in negligence.

While a fairly good number of actions in defamation have been decided by the Ghanaian courts for publications that have allegedly violated a person’s right to privacy and negatively impacted the reputation of the claimant, there are only a handful of cases based purely on the violation of privacy.

However, it is conceded that the resolution of these issues in certain instances may not be so clear-cut as the publisher of content may be said to have acquired copyright interests in the published content. It was my view that given the judicial position in the cases discussed in this article on the scope of the right to privacy, an action for the enforcement of the right to privacy would succeed.

[1] Garner, B. A (2004). Black’s Law Dictionary. 8th Edn

[2] Chitwood, A. (2021, November 22). J.K. Rowling’s home address was posted on Twitter. TheWrap. https://www.thewrap.com/jk-rowling-home-address-posted-to-twitter-doxxed-response/

[3] Sarikakis, K., & Winter, L. (2017). Social Media Users’ Legal Consciousness About Privacy. Social Media + Society, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117695325

[4] Jenny Steele (2007) Tort Law: Text, Cases and Materials. Oxford University Press

[5] Warren, S. D., & Brandeis, L. D. (1890). The Right to Privacy. Harvard Law Review, 4(5), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.2307/1321160

[6] Lunney, M., Nolan, D., & Oliphant, K. (2017-09-14). Tort Law: Text and Materials. Oxford: Oxford University Press Second Edition

[7] In EDEM ADINYIRA V. SCANCOM LTD & ANOR (2016) JELR 108252 (HC) it was held that a network provider’s disclosure of the phone records of a consumer to a third party was a negligent act.

[8] Chester, Simon, Murphy, Jason, & Robb, Eric. (2003). Zapping the paparazzi: is the tort of privacy alive and well. Advocates’ Quarterly, 27(4), 357-393.

[9] William Prosser (1960). ‘Privacy” 48 Cal L Rev 383, 386-9

[10] Summary. ALRC. (n.d.). https://www.alrc.gov.au/publication/serious-invasions-of-privacy-in-the-digital-era-alrc-report-123/6-reasonable-expectation-of-privacy/summary-164/

[11] RAPHAEL CUBAGEE V. MICHAEL YEBOAH ASARE, K. GYASI COMPANY LIMITED, ASSEMBLY OF GOD CHURCH (2018) JELR 68856 (SC). In this case, the court had to decide whether the recording of a private conversation without the consent of the other party was admissible in court. The court held that it would be wrong for the person at the other end to assume that the speaker has waived his rights of privacy and consented to him recording the conversation and rendering it in a permanent state. Therefore, to record someone with whom you are having a telephone conversation is to interfere with his privacy beyond what he has consented to.

[12] David Feldman (2002), Civil Liberties and Human Rights in England and Wales (2nd ed, Oxford: OUP), 762-6

[13] NEW PATRIOTIC PARTY V. INSPECTOR-GENERAL OF POLICE (1993) JELR 67912 (SC)

[14] Ghana Independent Broadcasters Association v The Attorney General and National Media Commission (2016) JELR 68165 (SC)

[15] Nana Yaa Asantewa-Danquah v. Scancom Limited (2011) JELR 110455 (CA)

[16] Supra 11

[17] Jemimah Wambui Ikere & another v. Standard Group Limited & another (2019) JELR 101014 (CA)

[18] Article 21 (1) (a) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana states that “All persons shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression, which shall include freedom of the press and other media”

[19] “1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This Article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television, or cinema enterprises. 2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions, or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.”

[20] LINGENS V. AUSTRIA (1986) JELR 111521

[21] Derbyshire County Council v. Times Newspapers Ltd (1993) JELR 111522 (HL)

[22] GHANA INDEPENDENT BROADCASTERS ASSOCIATION V. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL AND NATIONAL MEDIA COMMISSION (2016) JELR 68165 (SC)

[23] 1992 Constitution of Ghana

[24] FREEDOM SOWUBO v. THE DIRECTOR GENERAL OF PRISONS (2020) JELR 107260 (HC)