Background

In 2021, LGBT+ Rights Ghana, a movement championing the freedom of LGBT+ persons in Ghana had to shut down a community Centre meant to provide support for persons who identify as LQBT+ [1]. The closure of the Centre was a result of the public outrage sparked by the establishment of the Centre.

At the forefront of the resistance to the Centre was a coalition of the major religious groups and some anti-gay rights organizations who called on the State to resist the activities of LGBT+ Rights Ghana which they allege is an imposition of Western Culture on the Ghanaian Society.

The position of these associations reflects the general sentiment of a greater part of the Ghanaian society which is largely conservative[2]. In response to calls from the public, Ghana’s parliament passed a Bill, Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill, to provide a comprehensive and robust legal framework to crack down on LGBT+ activities [3].

This article will first review key provisions of the Bill and then discuss some of the constitutional issues raised by the passage of the Bill namely the right of parliament to regulate private morality and sexuality. Finally, the effect of the President’s refusal to assent to the Bill will be discussed.

The Bill and the Existing law

Before the passage of this Bill, the Criminal Offences Act [4] regulated some sexual behaviours. The law prohibits certain classes of sexual expression such as sexual intercourse with a close relative, incest, or bestiality. The Criminal Act even goes further to state some sexual acts as natural or unnatural carnal knowledge. The Act defines unnatural carnal knowledge as sexual intercourse with a person in an unnatural manner or with an animal[5].

Although the statutory definition is vague, the Supreme Court in Banousin v The Republic [6] said that

“It is the female sex organs called the vulva and vagina that are normally penetrated into during any sexual act which can qualify to be carnal knowledge under sections 98 and 99 of Act 29”. In sum under Ghanaian law, there is a notion that “natural” sexual activities are those between a male and a female.

The Bill[7] seeks to expressly proscribe LGBTQ+ activities and support victims of these acts. This is to be achieved by proscribing all forms of advocacy and promotion of the said activities. The Bill is made up of 25 sections beginning with an application and definition section which explains terms like gender, Ghanaian and proper human sexual rights.

It also imposes a duty on citizens to protect the proper human sexual rights and Ghanaian values it has described. In addition, citizens are to repost the commission of any of the offences in the Bill to either the police or political leaders of the community who will later report to the police.

The Bill further criminalizes the commission of acts amounting to procuration, detention with intent to cause a person to engage in prohibited sexual activities, and gross indecency which relates to a public show of amorous relationship between persons of the same sex. The Bill also wishes to declare any marriage outside of marriage between a man and a woman as void.

There is also a restriction on propaganda and advocacy of LGBTQ+ activities through all forms of media particularly those directed at children. At the coming into force of the Bill all LGBTQ+ groups will be disbanded, and no person will be able to sponsor their activities without incurring criminal liability. The Bill also grants access to medical care to persons found liable for any of the acts prohibited in the Bill only after they recant openly the offending identity or their stance.

Can Parliament regulate private morality and sexuality?

The Constitution of Ghana vests the legislative power of Ghana in Parliament[8]. This right is exercised through the passage of Bills which will become law after the President assents to it.

There, however, is a constitutional requirement that this power be exercised in accordance with the Constitution. That is, the laws made must not be inconsistent with or contravene a provision of the Constitution[9] which is the supreme law.

In Food Sovereignty v Attorney-General [10], the Supreme Court restated the position of the laws as follows;

“Parliament has the fullest legislative power, subject only to what the Constitution prohibits, expressly or impliedly. Thus, so far as there is no express or implied prohibition in the constitution of a particular subject or a thing that Parliament cannot legislate, it has all the powers to enact any law as it so wishes”.

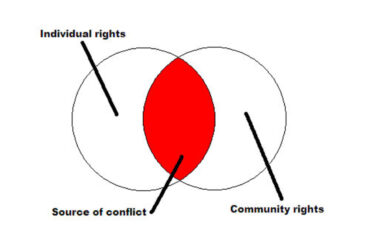

At first glance, the Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill seems to interfere with the enjoyment of certain constitutionally guaranteed rights notably the right of freedom of expression[11], the right to legal representation[12], and the right of association[13] amongst others which the Supreme Court has upheld in various decided cases. However, the promoters of the Bill counterargue in the Memorandum of the Bill that the fundamental human rights granted by the Constitution are not absolute.

Specifically, these rights must be exercised while respecting the rights and freedoms of others and for the public interest[14]. Additionally, there may be reasonable restrictions on the enjoyment of rights where necessary for public health, order, or safety[15]. To them therefore the Bill is preserving the public interest of preserving the concept of the family, which is a union between a man and a woman, as recognized and celebrated by all the ethnic groups in Ghana.

The arguments for the Bill reflect Devlin’s arguments on private and public morality[16]. Devlin[17], argues for the position that the law can regulate private morality on grounds that laws are based on common beliefs of morality and the laws ought to mirror these moral convictions and defend their social environment from anything that threatens their social environment. He argues that this type of moral question is unlike religious ones which cannot be imposed on other members of society, it is rather a type of morality which must be conformed to safeguard the community’s existence.

Ultimately, it is a question the Supreme Court must answer and declare which side of the argument is valid from a proper interpretation of the Constitution even if the matter has a political undertone [18]. Unsurprisingly, no sooner had the Bill been passed was the Supreme Court posed with the question of its validity or otherwise [19]. The determination of the constitutionality of a Bill which is yet to become law [20] is premised on reasons such as what was expressed in Yeboah v J.H Mensah [21],

“… any person who fears a threatened breach of the fundamental law [can] invoke our enforcement jurisdiction in a sort of quia timet action to avert the intended or threatened infringement of the Constitution. This is because our enforcement jurisdiction is premised upon the consideration that, to quote from the Memorandum on the 1969 Constitution, ‘any person who fears a threatened infringement or alleges an infringement of any provision of the Constitution’ should be able to seek redress in this court.”

From the Food Sovereignty Ghana case, the petitioner must also “demonstrate clearly that the acts or omission complained of are inconsistent with particular provisions of the Constitution” for the court to invoke itsinterpretative or enforcement jurisdiction.

It may be instructive to note that the Supreme Court in the Food Sovereignty Case[22] has expressed its reluctance to evoke its enforcement jurisdiction where a matter is to strike down an Act of parliament which has been made according to the legislature’s constitutional powers and which does not offend the Constitution simply because the law is undesirable or makes a section of the population unhappy.

The President’s refusal to assent to the Bill.

Given the President’s reluctance to sign the Bill, he must either inform the Speaker of Parliament that he has referred the Bill to the Council of State for consideration or in a memorandum addressed to the Speaker state any specific provisions he believes ought to be reconsidered by Parliament including his recommendations for amendments [23].

Parliament must then reconsider the Bill taking into account the comments made by the President or the Council of State. Where the reconsidered Bill is passed by a resolution supported by the votes of at least two-thirds of all members of Parliament, the President is bound to assent to it within thirty days. Should the President still refuse to assent to the Bill thirty days after the resolution is passed, the Supreme Court may issue a mandamus to lie against him to compel him to perform his public duty [24]. Where this order is not complied with, the President can be removed from office for committing a high crime [25].

What the future holds

The safety of people who identify or are tagged as LGBTQ+ persons may be in jeopardy if the Bill becomes law. Findings [26] show that LBGBTQ+ persons and people suspected of being LGBT+ person face severe harassment which usually culminates into physical assault. It is feared that the passage of the Bill will worsen these attacks regardless of the provision that criminalizes these mob actions. It is also likely that the other members of the community will be reluctant to give up those who participate in these attacks to the police because they also abhor LGBTQ+ activities.

Also, the general well-being of the community may be at risk. Some research findings have shown a resurgence of the HIV pandemic, particularly among LGBTQ+ persons. Thus, the probability that persons living with HIV/AIDS will refrain from seeking medical health for fear of both social and legal repercussions of being tagged as an LGBTQ+ person is high.

Already some of the country’s international allies have expressed their disappointment and concern over the passage of the Bill. On one hand, they urge the President not to assent to the Bill while some international partners have hinted at the probability of them withdrawing the aid they provide. Some lawmakers who supported the Bill have also alleged that they now face stricter restrictions when it comes to international travel because of their position on the Bill. The consequence of losing[27] some of this financial support will be devastating for the general population because this aid supports social welfare structures and benefits like the National Health Insurance Scheme.

Conclusion

The Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill, passed to provide a legal framework to respond to LGBTQ+ activities, raises legal questions about the infringement of some fundamental human rights which have been entrenched in Ghana’s Constitution. The promoters of the Bill, however, insist that because these rights were not guaranteed absolutely, their enjoyment can be interfered with if done under the law.

In sum, Parliament has the power to make laws to govern any subject matter except for matters expressly prohibited by the Constitution. They must however ensure that the laws made are consistent with the highest law in Ghana, the constitution, to prevent the Supreme Court from declaring it as void. The President, representing the executive, must also assent to Bills passed by Parliament before they can come into force. This relationship between the three arms of government is in line with the doctrine of separation of powers.

Regardless of the position the Supreme Court takes, it is undeniable that the provisions of the Bill are excessive and can create hardships for LQBTQ+ persons.

[1] Guardian News and Media. (2021, February 25). Ghanaian LGBTQ+ Centre closes after threats and abuse. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/feb/25/lgbtq-ghanaians-under-threat-after-backlash-against-new-support-centre

LGBTI centre forced to close its doors after police raid; journalist arrested. Civicus Monitor. (n.d.-b). https://monitor.civicus.org/explore/lgbti-centre-forced-close-its-doors-after-police-raid-journalist-arrested/

[2] Isaack, W. (2023, March 28). “no choice but to deny who I am.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/01/08/no-choice-deny-who-i-am/violence-and-discrimination-against-lgbt-people-ghana

[3] Naadi, T. (2024, February 28). Ghana passes bill making identifying as LGBTQ+ illegal. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-68353437

[4] THE CRIMINAL OFFENCES ACT,1960 (ACT 29)

[5] SECTION 104(2) OF ACT 29

[6] RICHARD BANOUSIN V. THE REPUBLIC (2015) JELR 68931 (SC)

[7] THE LONG TITLE OF THE BILL

[8] Article 93 of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

[9] Article 1(2) and 2(1)

[10] FOOD SOVEREIGNTY GHANA VS ATTORNEY-GENERAL (2023) JELR 111292 (SC)

[11] GHANA INDEPENDENT BROADCASTERS ASSOCIATION V. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL AND NATIONAL MEDIA COMMISSION (2016) JELR 68165 (SC)

[12] ELIZABETH AGBENORXEVI v. ACCRA BREWERY LIMITED (2019) JELR 107223 (HC)

[13] MENSIMA AND OTHERS v. ATTORNEY-GENERAL AND OTHERS JELR 85265 (SC)

[14] ARTICLE 12(2) OF THE 1992 CONSTITUTION OF GHANA

[15] ARTICLE 21(4) (C)

[16] In the 19, England sought to reform its laws on. To ascertaining the public’s view on the state of the law, the Wolfenden Committee was set up. Their recommendation was that they recommended that homosexual behaviour between consenting adults in private should no longer be a criminal offence.

[17] Dworkin, R. (1966). Lord Devlin and the Enforcement of Morals. The Yale Law Journal, 75(6), 986–1005. https://doi.org/10.2307/794893

[18] MENSAH v. ATTORNEY-GENERAL (1997) JELR 80617 (SC)

[19] Richard Sky files suit at Supreme Court seeking to declare “Anti-LGBTQI+ Bill” unconstitutional – The Herald ghana

[20] ARTICLE 106 OF THE 1992 CONSTITUTION

[21] MICHAEL YEBOAH V. JOSEPH HENRY MENSAH (1998) JELR 68195 (SC)

[22] SUPRA No 10

[23] ARTICLE 106 OF THE 1992 CONSTITUTION OF GHANA

[24] SALLAH V ATTORNEY GENERAL (1970) GLR

[25] ARTICLE 2 (5) OF THE 1992 CONSTITUTION OF GHANA

[26] Isaack, W. (2023, March 28). “no choice but to deny who I am.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/01/08/no-choice-deny-who-i-am/violence-and-discrimination-against-lgbt-people-ghana

[27] Thomas Naadi in Accra & Gianluca Avagnina in London. (2024, March 4). Ghana’s Finance Ministry urges president not to sign anti-LGBTQ+ Bill. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-68469613

Finance Ministry’s document on implications of LGBT+ bill shows its incompetency – pianim. GhanaWeb. (2024, March 9). https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/business/Finance-Ministry-s-document-on-implications-of-LGBTQ-bill-shows-its-incompetency-Pianim-1920634